Ramsay

It should not be supposed that this division of the notes into semitones, as we call them, is something invented by man; it is only something observed by him. The cutting of the notes into twelve semitones is Nature's own doing. She guides us to it in passing from one scale to another as she builds them up. When we pass, for example, from the key of C to the key of G, Nature divides one of the intervals into two nearly equal parts. This operation we mark by putting a # to F. We do not put the # to F to make it sharp, but to show [Scientific Basis and Build of Music, page 47]

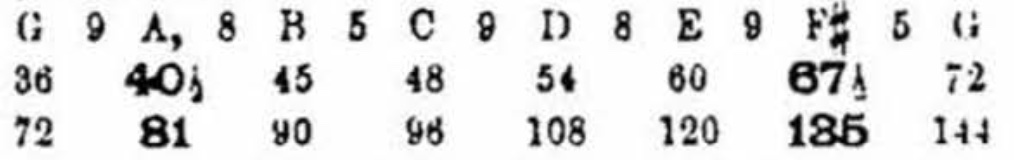

that Nature has done so.1 And in every new key into which we modulate Nature performs the same operation, till in the course of the twelve scales she has cut every greater note into two, and made the notes of the scale into twelve instead of seven. These we, as a matter of convenience, call semitones; though they are really as much tones as are the small intervals which Nature gave us in the Genesis of the first scale between B-C and E-F. She only repeats the operation for every new key which she had performed at the very first. It is a new key, indeed, but exactly like the first. The 5 and 9 commas interval between E and G becomes a 9 and 5 comma interval; and this Nature does by the rule which rests in the ear, and is uttered in the obedient voice, and not by any mathematical authority from without. She cuts the 9-comma step F to G into two, and leaving 5 commas as the last interval of the new key of G, precisely as she had made 5 commas between B and C as the last interval of the key of C, she adds the other 4 commas to the 5-comma step E to F, which makes this second-last step a 9-comma step, precisely as she had made it in the key of C.2 [Scientific Basis and Build of Music, page 48]

The various raisings and lowerings of notes in advancing keys, major and minor. - In each fifth of the majors ascending the top of the dominant is raised a comma. A40 in the key of C becomes A40 1/2 in the key of G; E60 in the scale of G is E60 3/4 in the scale of D; B90 in the scale of D is B91 1/8 in the scale of A. This alteration of the top of the dominant major goes on through all the twelve scales. Similarly, by the Law of Duality, each fifth in the minors descending has the root of the subdominant lowered a comma. D54 in the key of E minor is D53 1/2 in the key of A; G72 in the scale of A is G71 1/9 in the scale of D; C48 in the scale of D is C47 11/27 in the scale of G. This alteration of the root of the subdominant goes on through all the twelve minor scales. [Scientific Basis and Build of Music, page 62]

In just such a manner, only by more obvious leaps, the middle of the dominant in the advancing major scales is raised a sharp - i.e., four commas. When D27, the dominant top of the key of C, is multiplied by 5, it generates F#135; so, taking it one octave lower, F64 in C major is F#67 1/2 in the key of G. C96 in the key of G is C#101 1/4 in the key of D; G72 in the key of D is G#151 7/8 in the key of A. And this raising of the middle of the dominant goes on through all the twelve major keys.[Scientific Basis and Build of Music, page 62]

In the same way, but inversely, and still under the Law of Duality, the middle of the subdominant minor is lowered a flat. F#67 1/2 in the key of E minor is F64 in the key of A; B45 in the key of A is B?42 2/3 in the key of D; E60 in the key of D is E?56 8/9 in the key of G. This lowering by flats of the subdominant middle in the minors, responsive to the raising by sharps of the dominant middle in the majors, goes on through all the twelve minor keys.1 [Scientific Basis and Build of Music, page 62]

N.B. - The sharp comes here by the prime 5, and the comma by the prime 3. Now we have the key of G provided for;-

These are two octaves of the scale of G. G A B, which in the scale of C was an 8-9-comma third, must now take the place of C D E, which in C was a 9-6-comma [Scientific Basis and Build of Music, page 82]

VIOLIN-FINGERING - Whenever the third finger is normally fourth for its own open string, then the passage from the third finger to the next higher open string is always in the ratio of 8:9; and if the key requires that such passage should be a 9:10 interval, it requires to be done by the little finger on the same string, because the next higher open string is a comma too high, as would be the case with the E string in the key of G.

In the key of C on the violin you cannot play on the open A and E strings; you must pitch all the notes in the scale higher if you want to get [Scientific Basis and Build of Music, page 99]

Whenever a sharp comes in in making a new key - that is, the last sharp necessary to make the new key - the middle of the chord in major keys with sharps is raised by the sharp, and the top of the same chord by a comma. Thus when pausing from the key of C to the key of G, when F is made sharp A is raised a comma. When C is made sharp in the key of D, then E is raised a comma, and you can use the first open string. When G is made sharp for the key of A, then B is raised a comma. When D is made sharp for the key of E, then F# is raised a comma; so that in the key of G you can use all the open strings except the first - that is, E. In the key of D you can use all the open strings. In the key of A you can use the first, second, and third strings open, but not the fourth, as G is sharp. In the key of E you can use the first and second open. [Scientific Basis and Build of Music, page 100]

When Leonhard Euler, the distinguished mathematician of the eighteenth century, wrote his essay on a New Theory of Music, Fuss remarks - "It has no great success, as it contained too much geometry for musicians, and too much music for geometers." There was a reason which Fuss was not seemingly able to observe, namely, that while it had hold of some very precious musical truth it also put forth some error, and error is always a hindrance to true progress. Euler did good service, however. In his letters to a German Princess on his theory of music he showed the true use of the mathematical primes 2, 3, and 5, but debarred the use of 7, saying, "Were we to introduce the number 7, the tones of an octave would be increased." It was wise in the great mathematician to hold his hand from adding other notes. It is always dangerous to offer strange fire on the altar. He very clearly set forth that while 2 has an unlimited use in producing Octaves, 3 must be limited to its use 3 times in producing Fifths. This was right, for in producing a fourth Fifth it is not a Fifth for the scale. But Euler erred in attempting to generate the semitonic scale of 12 notes by the use of the power of 5 a second time on the original materials. It produces F# right enough; for D27 by 5 gives 135, which is the number for F#. D27 is the note by which F# is produced, because D is right for this process in its unaltered condition. But when Euler proceeds further to use the prime 5 on the middles, A, E, and B, and F#, in their original and unaltered state, he quite errs, and produces all the sharpened notes too low. C# for the key of D is not got by applying 5 to A40, as it is in its birthplace; A40 has already been altered for the key of G by a comma, and is A40 1/2 before it is used for producing its third; it is A40 1/2 that, multiplied by 5, gives C#202 1/2, not C200, as Euler makes C#. Things are in the same condition with E before G# is wanted for the key of A. G# is found by 5 applied to E; not E in its original and unaltered state, E30; but as already raised a comma for the key of D, E30 3/8; so G# is not 300, as Euler has it, but 303 3/4. Euler next, by the same erroneous methods, proceeds to generate D# from B45, its birthplace number; but before D# is wanted for the key of E, B has been raised a comma, and is no longer B45, but B45 9/16, and this multiplied by 5 gives D#227 13/16, not D225, as Euler gives it. The last semitone which he generates to complete his 12 semitones is B?; that is A#, properly speaking, for this series, and he generates it from F#135; but this already altered note, before A# is wanted for the key of B, has been again raised a comma [Scientific Basis and Build of Music, page 107]

This is a twofold mathematical table of the masculine and feminine modes of the twelve scales, the so-called major and relative minor. The minor is set a minor third below the major in every pair, so that the figures in which they are the same may be beside each other; and in this arrangement, in the fourth column in which the figures of the major second stand over the minor fourth, is shown in each pair the sexual note, the minor being always a comma lower than the major. An index finger points to this distinctive note. The note, however, which is here seen as the distinction of the feminine mode, is found in the sixth of the preceding masculine scale in every case, except in the first, where the note is D26 2/3. D is the Fourth of the octave scale of A minor, and the Second of the octave scale of C major. It is only on this note that the two modes differ; the major Second and the minor Fourth are the sexual notes in which each is itself, and not the other. Down this column of seconds and fourths will be seen this sexual distinction through all the twelve scales, they being in this table wholly developed upward by sharps. The minor is always left this comma behind by the comma-advance of the major. The major A in the key of C is 40, but in the key of G it has been advanced to 40 1/2; while in the key of E, this relative minor to G, the A is still 40, a comma lower, and thus it is all the way through the relative scales. This note is found by her own downward Genesis from B, the top of the feminine dominant. But it will be remembered that this same B is the middle of the dominant of the masculine, and so the whole feminine mode is seen to be not a terminal, but a lateral outgrowth from the masculine. Compare Plate II., where the whole twofold yet continuous Genesis is seen. The mathematical numbers in which the vibration-ratios are expressed are not those of concert pitch, but those in which they appear in the genesis of the scale which begins from F1, for the sake of having the simplest expression of numbers; and it is this series of numbers which is used, for the most part, in this work. It must not be supposed, however, by the young student that there is any necessity for this arrangement. The unit from which to begin may be any number; it may, if he chooses, be the concert-pitch-number of F. But let him take good heed that when he has decided what his unit will be there is no more coming and going, no more choosing by him; Nature comes in [Scientific Basis and Build of Music, page 117]

Hughes

The modulating gamut

—One series of the twelve keys meeting by fifths through seven octaves

—Keys not mingled

—A table of the key-notes and their trinities thus meeting

—The fourths not isolated

—The table of the twelve scales meeting by fifths

—The twelve keys, trinities, scales, and chords thus meeting are written in musical clef

—The twelve meeting through seven circles, each circle representing the eighteen tones

—The keys of C and G meeting, coloured

—Retrospection of the various major developments, . . . . 29 [Harmonies of Tones and Colours, Table of Contents3 - Harmonies]

THE twelve keys have been traced following each other seven times through seven octaves, the keys mingled, the thirteenth note being the octave, and becoming first of each rising twelve. Thus developing, the seven notes of each eighth key were complementary pairs, with the seven notes of each eighth key below, and one series of the twelve keys may be traced, all meeting in succession, not mingled. When the notes not required for each of the twelve thus meeting are kept under, the eighths of the twelve all meet by fifths, and as before, in succession, each key increases by one sharp, the keys with flats following, each decreasing by one flat; after this, the octave of the first C would follow and begin a higher series. It is most interesting to trace the fourths, no longer isolated, but meeting each other, having risen through the progression of the keys to higher harmonies. In the seven of C, B is the isolated fourth, meeting F#, the isolated fourth in the key of G, and so on. Each ascending key-note becomes the root of the fifth key-note higher; thus C becomes the root of G, &c. [Harmonies of Tones and Colours, Diagram VII - The Modulating Gamut of the Twelve Keys1, page 29]

The keys of C and G meeting are coloured, and show the beautiful results of colours arising from gradual progression when meeting by fifths. Each key-note and its trinities have been traced as complete in itself, and all knit into each other, the seven of each rising a tone and developing seven times through seven octaves, the keys mingled. The twelve scales have been traced, developing seven times through seven octaves, all knit into each other and into the key-notes and their trinities. The chords have also been traced, each complete in itself, and all knit into each other and into the key-notes, trinities, and scales. And lastly, one series of the twelve keys, no longer mingled, but modulating into each other, have been traced, closely linked into each other by fifths through seven octaves, three keys always meeting. Mark the number of notes thus linked together, and endeavour to imagine this number of tones meeting from the various notes. [Harmonies of Tones and Colours, The Twelve Scales Meeting by Fifths, page 31a]

Ascending, begin with C in the innermost circle, F being its root. The Key-note C becomes the root of G, G becomes the root of D, and so on. In descending, begin with the octave Key-note C in the outermost circle. F, the root of C, becomes the fifth lower Key-note. F is the next Key-note, and becomes the root of B?, &c. The 12 Keys in their order are written in musical clef below. Lastly, the Keys of C and G, ascending on a keyed instrument, are written in music as descending; therefore, to shew correctly notes and colours meeting, it is necessary to reverse them, and write C below G. All are seen to be complementary pairs in tones and colours. [Harmonies of Tones and Colours, Diagram VII Continued2, page 31e]

See Also

key

scale

scale of G

key of A

key of A flat

key of C

key of D flat

key of E

key of F

key of F sharp

key of G

progression of keys

root of the fifth higher keynote

root of the fifth keynote

The Major Keynote of C