Henry Ford (July 30, 1863 - April 7, 1947) was a prominent American industrialist, the founder of the Ford Motor Company, and sponsor of the development of the assembly line technique of mass production. His introduction of the Model T automobile revolutionized transportation and American industry. As owner of the Ford Motor Company, he became one of the richest and best-known people in the world. He is credited with "Fordism": mass production of inexpensive goods coupled with high wages for workers. Ford had a global vision, with consumerism as the key to peace. His intense commitment to systematically lowering costs resulted in many technical and business innovations, including a franchise system that put a dealership in every city in North America, and in major cities on six continents. Ford left most of his vast wealth to the Ford Foundation but arranged for his family to control the company permanently (until it was taken over by outsiders).

He was known worldwide especially in the 1920s for a system of Fordism that seemed to promise modernity, high wages and cheap but high quality consumer goods. (wikipedia)

American industrialist and business tycoon Henry Ford resigns from his position as chief engineer at Edison Illuminating Company in Detroit, Michigan on August 15, 1899 to start his own automobile factory.

By the time Ford resigned from Edison, he had already developed three automobiles in his home workshop and created a new carburetor that was patented.

The first automobile company that Ford founded was the Detroit Automobile Company. Unfortunately, the automobiles made were of lower quality and higher priced than what Ford wanted to produce, and the company dissolved in January 1901.

Just under one year later, Ford founded the Henry Ford Company in November 1901, which was reincorporated as the Ford Motor Company in 1903.

With the help of investors and the Dodge brothers, John and Horace E., Ford was able to produce a quality automobile at an affordable price for the everyday American.

That automobile was the Model T which debuted in October 1908.

Additionally, Ford developed the modern-day assembly line, which revolutionized factory production.

April 7, 1947, pioneer of the automobile, Henry Ford, died at his estate in Dearborn, Michigan. Born on a farm in 1863, Ford, the eldest child of his family, spent much of his teenage years working as an apprentice machinist in the city of Detroit. Ford later became an engineer, and during the 1890s, he began experimenting with the internal combustion engine, developing a gas powered, self-propelled vehicle in 1896 that he called the “Quadricycle.” From that point on, Ford was obsessed with coming up with a successful way to manufacture these vehicles cheaply, efficiently, and in large enough numbers that the general public could afford them.

In 1903, after two failed attempts, he founded the Ford Motor Company, which just a few years later came out with the Model T, a cheap, mass produced, easy to drive, easy to maintain vehicle. It was an instant hit. Within ten years, half of the cars on the road were Model Ts. In addition to the automobiles themselves, Ford also revolutionized the factories producing them. His factories featured a moving assembly line where each worker stayed in place and had an assigned part to add to the car. At its peak, the Ford Factory could build an entire car in only 93 minutes. Also, Ford became the first to introduce the minimum wage and the first to establish a set eight-hour workday. Most other auto makers paid half that much and had their employees work a nine-hour day. In the end, Henry Ford’s innovation of the fair wage made it possible for the workers to actually buy the cars they made, creating in part the American middle class as we know it today.

On October 7, 1913, Henry Ford’s entire Highland Park, Michigan automobile factory ran a continuously moving assembly line for the first time. A motor and rope pulled the chassis past workers and parts on the factory floor, cutting the man-hours required to complete one Ford Model T from 12 1/2 hours to six. Within a year, further assembly line improvements reduced the time required to 93 man-minutes.

The staggering increase in productivity resulting from use of the moving assembly line allowed Ford to drastically reduce the cost of the Model T, thereby accomplishing his dream of making the car affordable to ordinary consumers. Before then, the automobile industry generally marketed its vehicles to only the richest Americans, because of the high cost of producing the machines. Ford’s Model T was the first automobile designed to serve the needs of middle-class citizens: It was durable, economical, and easy to operate and maintain. Still, with a debut price of $850, the Model T was out of the reach of most Americans. Ford Motor Company understood that to lower unit cost it had to increase productivity. The method by which this was accomplished transformed industry forever.

Prototypes of the assembly line can be traced back to ancient times, but the immediate precursor of Ford’s industrial technique was 19th-century meat-packing plants in Chicago and Cincinnati, where cows and hogs were slaughtered, dressed, and packed using overhead trolleys that took the meat from worker to worker. Inspired by the meat packers, Ford innovated new assembly line techniques and in early 1913 installed its first moving assembly line at Highland Park for the manufacture of flywheel magnetos (pictured). Instead of each worker assembling his own magneto, the assembly was divided into 29 operations performed by 29 men spaced along a moving belt. Average assembly time dropped from 20 minutes to 13 minutes and soon was down to five minutes.

Ford rapidly improved its assembly lines, and by 1916 the price of the Model T had fallen to $360, and sales were more than triple their 1912 level. Eventually, the company produced one Model T every 24 seconds, and the price fell below $300. More than 15 million Model Ts were built before it was discontinued in 1927, accounting for nearly half of all automobiles sold in the world to that date. The affordable Model T changed the landscape of America, hastening the move from rural to city life, and the moving assembly line spurred a new industrial revolution in factories around the world.

THOMAS EDISON AND HENRY FORD

In 1896, Thomas Edison, the great inventor who invented the electric bulb, was working on an idea to design a car when he heard that a young man who worked in his company had created an experimental car.

Edison met the youngman at his company's party in New York and interviewed him about the car. He was impressed! He had the same idea as the young man but he was considering electricity as the power source while the young man used gasoline engine to power the car. He slammed his fist down and shouted "young man, that's the thing! You have it! .. I think you are on to something! I encourage you to continue your pursuits!"

With these words of encouragement from the most highly respected inventor in the United States at that time, HENRY FORD, continued his work, invented a car and became wealthy.

On december 9, 1914, Thomas Edison's laboratory and factory got burnt. He was 67years old and the damage was too extensive for insurance cover. Before the ashes were cold, Henry Ford handed Edison a cheque of $750,000 with a note saying that Edison can have more if he needed it!

In 1916, Henry Ford relocated his home to the building next to Edison's home and when Edison couldn't walk and was confined to a wheelchair by his doctors, Henry Ford also bought a wheelchair in his house so that he could run wheelchair race with his friend and mentor!

Thomas Edison made Henry Ford believe in himself and got a friend for life!

Strongly recommended Ford biography: The Wild Wheel, by Garet Garrett, 1952, Pantheon Books, Inc., Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 52-7392 - review of this amazing book

download pdf

July 23 1903 - The First FORD Automobile Was Sold.

The original Ford Model A is the first car produced by the Ford Motor Company, beginning production in 1903. Ernest Pfennig, a Chicago dentist, became the first owner of a Model A on July 23, 1903; 1,750 cars were made from 1903 through 1904 during Ford's occupancy of its first facility: the Ford Mack Avenue Plant, a modest rented wood-frame building on Detroit's East Side. The Model A was replaced by the Ford Model C during 1904 with some sales overlap.

The car came as a two-seater runabout for $800 or the $900 four-seater tonneau model with an option to add a top.

The company had spent almost its entire $28,000 initial investment funds ($911,970 in 2022 dollars) with only $223.65 left in its bank account when the first Model A was sold. The success of this car model generated a profit for the Ford Motor Company, Henry Ford's first successful business.

Five years later Ford introduced the hugely influential Model T.

Photo: Henry Ford driving his 1903 Runabout Model A.

Kingsford Briquettes

Henry Ford was obsessed with building the Model-T as efficient and inexpensive as possible. To do that he used the process of Vertical Integration where Ford Motor Company created companies that supplied the factory with materials. Ford made their own steel, harvested rubber and built sawmills to supply lumber to the factory.

A few miles south of L’Anse on U.S. 41 is the town of Alberta where Henry Ford built a sawmill town in 1936 to supply lumber to his grown auto company. The town was named after the daughter of one of his executives. The community consisted of a sawmill, houses for the workers and their families, and two schools to educate the children while their parents were working.

Henry Ford saw all the sawdust that was created by his sawmills and felt it was going to waste. At his sawmill in Kingsford Michigan, named for Edward G. Kingsford who worked for Ford managing his lumbering operations, the mill created an enormous amount of sawdust. A University of Oregon chemist, Orin Stafford invented a method for making pillow-shaped lumps of fuel from sawdust and called them charcoal briquettes. Thomas Edison designed the briquette factory built next to the sawmill and Edward G. Kingsford managed it. Ford sold the briquettes at his dealerships and after world war II as the suburbs grew and the Webber grill became popular, the demand for the bags of black briquettes soared. Ford sold the company in 1951 and it was renamed Kingsford in honor of Edward G. Kingsford.

In 1954 the town of Alberta was donated to Michigan Tech and is still used today for forestry education. If you’re in the area they give tours of the historic town and sawmill to visitors.

December 10, 1915 – The 1,000,000th Ford

Henry Ford had one goal: put the world on wheels. To be able to provide the masses with a car both reliable and affordable by the average worker, Henry had to solve two complex problems. First, he had to create the car, in a brand new industry, that was simple to operate and required basic knowledge to care for. Second, he had to make a lot of them. His answer to issue A was the Model T, introduced in 1908. By focusing on one model he was able to enhance the efficiency of production, but the company still struggled to make enough to make them appealing to the average Joe’s bank account.

In 1909 a hair over 10,000 of the vehicles left the factory. By the end of 1912 Henry had all but perfected automobile manufacturing in a traditional sense. That year 68,773 units sold, allowing prices to drop from $825 in 1909 to $560 in 1912. Then, inspiration struck after observing production workers at a slaughter house and a brewery.

Bottling plants and slaughter houses moved product, not people, during operation. Ford implemented changes to his factories to reflect this style of manufacturing, thus solving the second roadblock to his goal. Ford’s revolutionary moving automobile assembly line came to life December 1, 1913. Model Ts began to roll out of the factory in record numbers; 1914 saw 202,667 built.

The mass production of the Model T only got faster, leading to a major milestone. On this day in 1915, the 1,000,000th Ford car left the factory. It had taken 7 years since the beginning of Model T production and 12 years of total Ford production, to get to this point. In the 12 more years the Model T would remain the staple of the Ford lineup, some 14 million more would be made. The last one left the factory on May 26, 1927, priced at just $360.

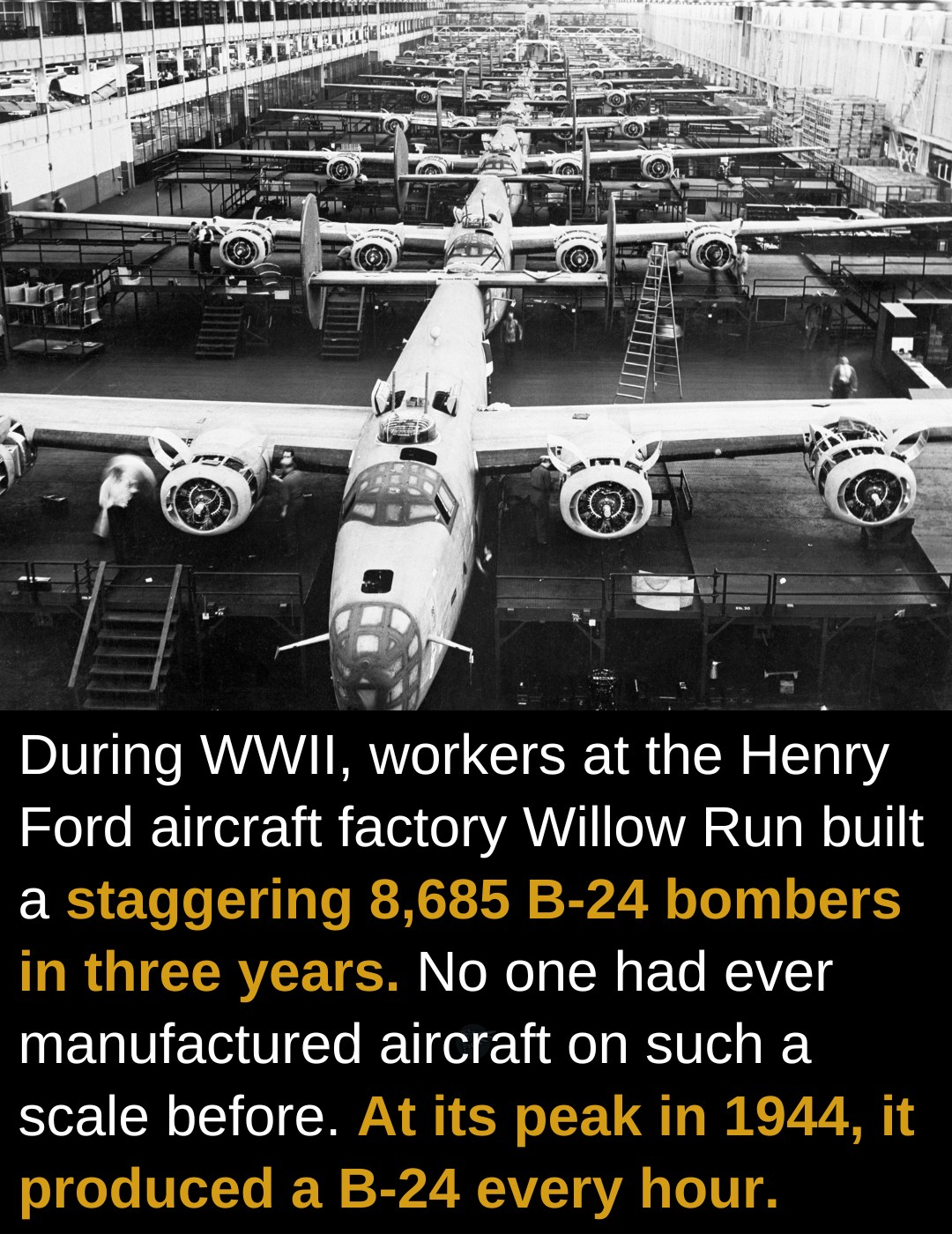

B-24 Liberator bomber airplanes

During World War II, the Ford Motor Company built 8,685 B-24 Liberator bomber airplanes at its Willow Run plant, 35 miles west of Detroit. By the spring of 1944, employees on Ford's bomber assembly line could turn out a finished airplane every 63 minutes. Workers completed the 6,000th B-24 in September 1944 with considerable fanfare.

Willow Run... by November 1943 they were rolling out a new B-24 every hour. At its peak monthly production (August 1944), Willow Run produced 428 B-24s with highest production listed as 100 completed Bombers flying away from Willow Run between April 24 and April 26, 1944. By 1945, Ford produced 70% of the B-24s in two 9-hour shifts. Ford built 6,972 of the 18,482 total B-24s and produced kits for 1,893 more to be assembled by the other manufacturers. The B-24 holds the distinction of being the most produced heavy bomber in history

https://planehistoria.com/atka-b-24-wreckage/

During World War II, something incredible happened just outside Detroit.

At a place called Willow Run, the Ford Motor Company took on a challenge that seemed nearly impossible—they built almost 9,000 B-24 Liberator bombers in just three years. No one had ever done anything like that before, not on that scale, and not that fast.

By 1944, the factory was turning out one bomber every single hour. That’s how fast they moved. It wasn’t just a factory anymore—it was the heart of what people called the “Arsenal of Democracy.” It showed the world that American industry could be as strong and steady as anything in nature—powerful, tireless, and unstoppable.

But the real story of Willow Run isn’t just about machines. It’s about the people.

Tens of thousands of workers—many of them women who had never worked in factories before—came together to build those planes. With their sleeves rolled up and bandanas tied back, they picked up tools and got to work. They weren’t just filling in for the men who went off to war—they were showing what they were capable of. This was where the spirit of “Rosie the Riveter” was born, not as a slogan, but as a reality.

Willow Run became more than a factory. It became a symbol of what people can do when they come together with purpose. It reminds us that in the face of crisis, unity, determination, and a shared sense of mission can change the course of history.

In 1944, a factory outside Detroit was doing something that seemed physically impossible—rolling a completed four-engine bomber off the assembly line every 63 minutes, 24 hours a day.

The Willow Run plant stretched over 3.5 million square feet—so vast that supervisors used bicycles to get from one end to the other. When Ford Motor Company agreed to build B-24 Liberators here, skeptics said it couldn't be done. These weren't cars. Each bomber required 1.2 million parts, 360,000 rivets, and precision that could mean life or death for the ten-man crews who would fly them into combat over Europe and the Pacific.

Henry Ford's engineers looked at the challenge and saw something others missed: if you could mass-produce a car, why not an airplane? They designed the world's longest assembly line and reimagined aircraft manufacturing from the ground up. Parts moved on conveyor belts. Subassemblies came together with automotive efficiency. What had taken scattered aviation companies weeks to build, Willow Run aimed to complete in hours.

The numbers tell an almost unbelievable story. By the time production hit its stride in 1944, Willow Run was producing one complete B-24 Liberator every 63 minutes. Workers attached 58,000 pounds of metal, wiring, engines, and armaments into a flying machine faster than most people today could assemble furniture. Over three years, nearly 8,700 bombers rolled out of that single factory—accounting for half of all B-24s built during the entire war.

But here's what the statistics can't fully capture: who built them.

At its peak, Willow Run employed over 40,000 workers. A third of them were women. Many had never touched a rivet gun before Pearl Harbor. They came from farms and kitchens, from small towns across Michigan and beyond, drawn by patriotic duty and paychecks that offered independence they'd never known. With bandanas holding back their hair and coveralls replacing dresses, they climbed into bomber fuselages, operated massive machinery, and proved that "women's work" was whatever work needed doing.

These were the real Rosies. Not a poster or a symbol, but actual women named Violet, Rose, and Eleanor who welded, drilled, and assembled with the same skill as any man. They worked swing shifts and graveyard shifts. They learned trades in weeks that typically took years. And they did it knowing that every rivet they placed, every wire they connected, might save the life of someone's son flying missions over Germany.

The factory operated around the clock. Three shifts kept the assembly line moving through day and night. When workers clocked out, others clocked in, and the work never stopped. The sound of riveting echoed constantly—a mechanical heartbeat that never paused, never rested, never quit until victory was won.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt called America "the Arsenal of Democracy," and Willow Run was its proving ground. Stalin himself acknowledged that the war was won not just on battlefields but in factories like this one. The B-24s built at Willow Run flew missions that turned the tide—bombing raids over Ploesti, supply runs over the Himalayas, anti-submarine patrols over the Atlantic.

When the war ended in 1945, production stopped. The workers went home. Many women returned to domestic life, their contributions quickly forgotten by a society eager to return to "normal." The factory eventually became a General Motors plant, and most of the original structure was demolished in 2013.

But what happened at Willow Run can never be demolished. It stands as proof that when a nation unites around a common purpose, when ordinary people are given the tools and trust to do extraordinary things, the impossible becomes routine. It reminds us that the greatest generation wasn't great because they were special—they were great because when their moment came, they rose to meet it.

One bomber every 63 minutes. Eight thousand six hundred eighty-five reasons why freedom prevailed. And tens of thousands of workers—many of them women who'd been told they couldn't—proving exactly what they could do when given the chance.

Trivia (is this true?)

We all know about Dodge cars but who knew that the Dodge brothers virtually built the first cars for ol' Henry (of Ford fame!)!

In 1897 the Dodge brothers, Horace and John, started building bicycles in Detroit, Michigan. They became very well known for design and innovation and caught the interest of a fella by the name of Ransome E. Olds. He was just getting into building the Curved Dash Oldsmobile automobile and he asked the brothers, who were already building auto parts for others, to build the power train for the new car line.

This was a success for all parties involved but it became a matter of great concern to another newcomer into the automobile field, Henry Ford. Henry was all hot to take over the Oldsmobile market share but to do that he needed a car to sell. His brainchild was the Model T but he had no parts. After much negotiation which ultimately cost him 10% of his new auto company the Dodge brothers began building car parts for Ford. These parts included almost everything it took to build the Model T.

About 1912 or so Henry decided that the brothers were becoming too powerful in the industry and tried to break them financially.

Remember the 10% share?

Henry lost in his attempt and ended up paying out Horace and John with enough money to start their own factory under the name of "Dodge Brothers".

Again their innovation proved itself when their first car off the line (they had actually invented the assembly line for Ford) had an all steel body, beating the competition by at least two decades. They also waxed the seat of Fords pants with a much better product than what Ford was selling. This included, but was not limited to, a 35 hp engine compared to the 20 hp of the Model T. For a time the Dodge Brothers automobile was at the top of the heap and everyone else was trying to play catch up. [anon]

On May 1, 1926, Ford Motor Company becomes one of the first companies in America to adopt a five-day, 40-hour week for workers in its automotive factories. The policy would be extended to Ford’s office workers the following August.

Henry Ford’s Detroit-based automobile company had broken ground in its labor policies before. In early 1914, against a backdrop of widespread unemployment and increasing labor unrest, Ford announced that it would pay its male factory workers a minimum wage of $5 per eight-hour day, upped from a previous rate of $2.34 for nine hours (the policy was adopted for female workers in 1916). The news shocked many in the industry—at the time, $5 per day was nearly double what the average auto worker made—but turned out to be a stroke of brilliance, immediately boosting productivity along the assembly line and building a sense of company loyalty and pride among Ford’s workers.

The decision to reduce the workweek from six to five days had originally been made in 1922. According to an article published in The New York Times that March, Edsel Ford, Henry’s son and the company’s president, explained that “Every man needs more than one day a week for rest and recreation….The Ford Company always has sought to promote an ideal home life for its employees. We believe that in order to live properly every man should have more time to spend with his family.”

Henry Ford said of the decision: “It is high time to rid ourselves of the notion that leisure for workmen is either ‘lost time’ or a class privilege.” At Ford’s own admission, however, the five-day workweek was also instituted in order to increase productivity: Though workers’ time on the job had decreased, they were expected to expend more effort while they were there. Manufacturers all over the country, and the world, soon followed Ford’s lead, and the Monday-to-Friday workweek became standard practice.

Fordlandia - The Jungle That Ate Ford's Dream

In 1927, Henry Ford had a wild idea. He'd build a piece of America right in the Amazon rain forest. Not just any town, but a perfect one. A place where his workers would live by his rules: no booze, lots of vegetables, and plenty of square dancing.

Ford called it Fordlandia. It was supposed to be a rubber plantation that would make tires for his cars. But it became so much more in his mind. He promised good pay, nice houses, and all the comforts of home to lure workers to this patch of Brazilian jungle.

But the Amazon had other plans. The rubber trees Ford planted got sick. The workers hated his rules. They even set up a secret spot called the 'Island of Innocence' where they could drink and have fun away from Ford's watchful eye.

The worst part? Ford never even set foot in Fordlandia. He just kept throwing money at it from afar. By the 1940s, after millions spent, not a single tire had rolled out of the jungle. Ford gave up, and nature took back what was hers.

Now, Fordlandia is a ghost town. Rusted machines sit quietly as vines creep over them. Empty buildings slowly crumble. It's like walking through a forgotten movie set where man's ambition collided head-on with the power of the rain forest.

Fordlandia stands as a strange reminder of what happens when someone tries to force their dream onto a world they don't understand.

Comment: It failed because he trusted the wrong people. [see Pond Family in Brazil]

Ford F-Series Trucks: The Ford F-150 has been the best-selling vehicle in the U.S. for over 40 years straight. Introduced in 1948, the F-Series reflects America’s love for rugged, versatile vehicles. In 2023 alone, Ford sold over 750,000 units, and it’s a cultural icon often tied to the American “open road” ethos.

Ford Philosophy

- “A manufacturer is not through with his customer when a sale is completed. He has then only started with his customer.” (Chapter II), followed by an explanation that a dissatisfied customer is “the worst of all advertisements.” [Project Gutenberg]

- “…for of course it is not the employer who pays wages. He only handles the money. It is the product that pays the wages and it is the management that arranges the production so that the product may pay the wages.” (Chapter V). [Project Gutenberg]

- In the same stretch he sums up his philosophy as, “For the only foundation of real business is service.” (Chapter II). [Project Gutenberg]

Taken together, Ford saw business as service and regarded himself as a steward/custodian of the public’s money—answerable to customers by building the best, most serviceable car he could.

The most powerful bankers in America walked into Henry Ford's office holding his future.

They walked out holding their hats.

December, 1920. Dearborn, Michigan.

The delegation from New York didn't bother hiding their confidence. Why would they? The numbers told the story.

Ford Motor Company: $58 million in debt due by spring. Cash available: $20 million.

The gap wasn't a problem to solve. It was a done deal.

They'd prepared generous terms. Extended repayment schedule. Reasonable interest. Just one requirement—a seat on Ford's board. Someone to ensure the money was protected. To provide "guidance."

Standard operating procedure when rescuing a company from itself.

Henry Ford listened quietly. Then stood, grabbed the nearest hat from the rack, and handed it to the lead banker.

"Meeting's over."

The men exchanged glances. The smile on the lead negotiator's face never wavered as they filed out.

Ford would call within a week. Maybe two. Desperation had a way of clarifying things.

They'd structured the deal assuming he'd refuse initially. Pride always came before the fall.

What they didn't know: Henry Ford had already decided he'd rather destroy everything he'd built than let a banker tell him what to do.

Ford had created his own nightmare.

Post-war expansion. River Rouge—$60 million for a factory complex so massive it had its own steel mill, glass plant, and power station. Another $15 million for iron ore and coal mines. Plants sprouting nationwide.

In 1919, drunk on success, he'd borrowed to buy out every minority shareholder. No more dividend demands. No interference. Pure autonomy.

Perfect—until the economy collapsed.

Post-war recession hit like a sledgehammer. Demand evaporated. Model T production costs exceeded sale prices by $20 per vehicle.

Making cars was now a money-losing operation.

But Ford couldn't stop production. Couldn't lay off workers and shut plants without admitting defeat. His ego wouldn't allow it.

By autumn 1920, bankruptcy wasn't a possibility. It was mathematics.

What Ford did next violated every principle of sound business management.

He attacked his dealers first.

No warning. No consultation. Just boxcars arriving at dealerships packed with Model Ts and spare parts nobody had ordered.

Bills attached. Cash on delivery. No credit terms.

"Pay up or turn in your franchise."

Dealerships were gold mines—everybody knew it. Dealers had invested years building customer bases. They weren't walking away.

So they scrambled. Borrowed from local banks. Liquidated personal assets. Some mortgaged their homes.

They paid. And they remembered.

Twenty-five million dollars came flooding back.

Ford moved to the railroad next. Bought the Detroit, Toledo & Ironton for five million—a failing line nobody wanted.

Not for profit. For speed.

He restructured routes to slash delivery times. Components that used to sit in transit for weeks now moved in days. Inventory turned over faster. Capital froze in warehouses suddenly became liquid.

Then he turned his attention inward.

Suppliers got ultimatums: slash prices or lose Ford's business. Payment schedules stretched from 60 to 90 days—without negotiation.

White-collar staff? Terminated. Office equipment? Liquidated. Ford held a massive sale—desks, filing cabinets, pencil sharpeners. Everything not bolted to the factory floor.

And then, the move that made competitors question his sanity.

In the middle of a recession, while hemorrhaging money on every vehicle, Ford announced the largest price cut in automotive history.

Model T prices dropped 20%. Below production cost.

General Motors' executives watched with satisfaction. Ford was finished. You don't survive selling products at a loss.

Except Ford wasn't chasing profit anymore.

He was chasing velocity. Moving inventory generated cash flow. Cash flow bought time. Time bought survival.

Profit could wait. Oxygen couldn't.

Ernest Kanzler understood what Ford was doing before anyone else.

Ford's production manager had pioneered efficiency methods at the Fordson tractor plant during the war. Now he applied that thinking across the entire operation.

The revelation was simple: money sitting in inventory was money you couldn't use.

So stop letting it sit.

Components arrived exactly when needed. No sooner. No excess warehousing. No capital trapped in spare parts gathering dust.

Highland Park had required 15 workers per completed car per day before the crisis.

By February 1921: 9 workers per car.

Forty percent reduction in labor costs. Not from technology improvements. From desperation forcing innovation.

The Japanese would later study these methods, refine them, call them "just-in-time manufacturing."

In 1920, Ford called it "not going bankrupt."

April, 1921.

The bankers received their payments. Full amount. On time. With interest.

No apology. No explanation. Just a check and a message: We're done.

Henry Ford had closed a $38 million gap in six months without borrowing a cent from Wall Street.

The bankers couldn't understand it. The math had been ironclad. Ford Motor Company should have collapsed.

What they'd miscalculated: Ford's willingness to do anything—squeeze suppliers, betray dealer trust, liquidate assets, sell products at a loss—to maintain independence.

They'd assumed he'd choose survival over pride.

He'd chosen both. On his terms.

There's a darker side to this story worth acknowledging.

Ford's dealers—many of them small business owners who'd bet everything on the franchise—never forgot being forced to take unwanted inventory. Some held grudges for decades.

His suppliers watched payment terms extend unilaterally. No negotiation. Accept it or lose the business.

His white-collar workers lost jobs not because the company failed, but because Ford refused to admit he'd over-extended.

Ford survived by distributing his pain to everyone around him. That's not heroism. That's ruthlessness.

But it worked.

And Ford learned something in 1920 he never forgot: Debt equals control. Whoever holds the debt holds power.

He spent the rest of his life ensuring nobody held that power over him again.

The 1920 crisis reveals something uncomfortable about success.

Sometimes winning requires willingness to do things others find unconscionable. Ford squeezed dealers who trusted him. Stiffed suppliers who'd built their businesses around his orders. Cut prices below cost while competitors played by rational rules.

The bankers operated by conventional wisdom: Companies in crisis accept terms. That's how the system works.

Ford rejected the system entirely.

When everyone agrees you're beaten, there's strange power in refusing to see it that way. The bankers calculated Ford's options and concluded he had none.

Ford found options they couldn't imagine because they required breaking every norm of business practice.

He won by being more ruthless than people expected. More stubborn than seemed rational. More willing to destroy relationships than anyone thought possible.

By 1921, Ford Motor Company stood alone.

Debt-free. Independently owned. More efficient than before the crisis.

The eastern bankers had their money. They had nothing else.

No influence. No board seat. No future leverage.

Henry Ford had looked at the most powerful financial institutions in America and said: I don't need you.

Then proved it.

Whether that makes him admirable or ruthless depends on whether you were Henry Ford—or one of the dealers forced to take inventory they couldn't sell.

But it's undeniably effective.

The world runs on debt. On leverage. On powerful institutions extending capital in exchange for control.

In 1920, one stubborn man decided he'd rather risk everything than participate in that system.

He won.

The bankers learned something that winter: Never bet against someone who'd rather lose their company than their autonomy.

Because that person isn't calculating odds.

They're fighting.

And people who refuse to lose are dangerous.

In early 1941, Charles Sorensen—Ford's production chief—visited a California aircraft plant where Consolidated Aircraft was building B-24 bombers.

He watched workers assemble planes outdoors, one at a time, using methods that hadn't changed in decades.

It was taking them a full day to build a single bomber.

That night, Sorensen sketched something on a piece of paper that would change the war.

A mile-long assembly line.

Bombers built like Model Ts.

One every hour.

The aircraft industry laughed.

Planes weren't cars. They had 488,193 parts, 313,000 rivets, and required constant design changes. You couldn't just throw untrained workers at wings and fuselages and expect them to fly.

Ford built it anyway.

On a tract of farmland near Ypsilanti, Michigan, they raised the largest factory in the world under a single roof. Three and a half million square feet. Eighty acres. The assembly line ran for a mile, then turned 90 degrees on massive turntables and kept going.

They called it Willow Run, after a creek that ran through the property.

The first Ford-built B-24 rolled off the line on October 1, 1942.

By December, they'd built 56 planes total.

Critics started calling it "Will It Run?"

Senator Harry Truman launched investigations. The press smelled failure. Ford's own people were drowning in chaos—Consolidated kept changing the blueprints, there weren't enough trained workers, and nobody could coordinate a factory this massive.

Then Edsel Ford—Henry's son—took charge.

He drove himself into the ground fixing it. He fought with his father. He fought with the Army. He fought with the unions.

On May 26, 1943, Edsel Ford died of cancer. He was 49 years old.

The stress of Willow Run had broken him.

But by then, something had changed.

The assembly line had found its rhythm.

In April 1944—two nine-hour shifts, six days a week—Willow Run produced 453 bombers in 468 hours.

One plane every 63 minutes.

Charles Sorensen's "preposterous" boast had come true.

At its peak, 42,000 people worked at Willow Run. Most of the men had been drafted. The workforce that replaced them wasn't seasoned machinists.

It was farmers' daughters. Widows. Mothers.

They'd never touched industrial equipment in their lives.

Rose Will Monroe was one of them.

She'd grown up in Kentucky, a tomboy handy with tools. When her husband was killed in a car accident, she moved to Michigan with her two young children, looking for work.

She wanted to be a pilot.

Willow Run disqualified her—single mothers couldn't enter the training program.

So Rose became a riveter instead.

One day, actor Walter Pidgeon visited the plant to film war bond propaganda. He needed someone to play a factory worker.

When he found out there was a woman named Rose who was actually a riveter, he cast her immediately.

Rose Will Monroe became the face of "Rosie the Riveter"—the most iconic image of American women in World War II.

But she wasn't alone. At peak production, one-third of Willow Run's workforce was women.

They wielded pneumatic rivet guns. They crawled inside wing sections. They installed 313,000 rivets per plane, 524 different types and sizes.

Ford even hired little people—recruited from circuses—to climb into spaces too tight for anyone else, bucking rivets inside wingtips.

By the time production ended in June 1945, Willow Run had built 8,685 B-24 Liberators—nearly half of all the B-24s ever made.

More than the four other factories combined.

The cost per plane dropped from $379,000 to $216,000.

And Rose Will Monroe?

At age 50, she finally got her pilot's license.

She flew her own plane until an engine failed during takeoff in 1978.

The crash cost her a kidney and the sight in one eye.

She never flew again.

But she'd proven what the women of Willow Run had proven every day on that mile-long assembly line:

When a nation's survival hangs in the balance, ordinary people do extraordinary things.

The critics called it "Will It Run?"

It ran.

See Also

8.28 - Creative

14.27 - Mind being Dominant is Creative

Chronology

Creation

Creative

Creative Force

Creative Forces

creativity as an anti-entropic principle

Ford Model T

Genius

George Washington Carver

Henry Ford, Wikipedia

John and Horace Dodge

Masterly Creating

Nikola Tesla

Part 24 - Awakening Your Genius

Scientific Creation