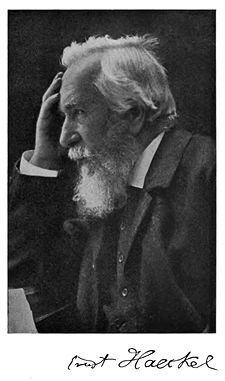

Eight theses on ether by Ernst Haeckel:

I. Ether fills the whole space, in so far as it is not occupied by ponderable matter, as a continuous substance; it fully occupies the space between the atoms of ponderable matter.

II. Ether has probably no chemical quality, and is not composed of atoms. If it be supposed that it consists of minute homogeneous atoms (for instance, indivisible etheric particles of a uniform size), it must be further supposed that there is something else between these atoms, either "empty space" or a third, completely unknown medium, a purely hypothetical "inter-ether"; the question as to the nature of this brings us back to the original difficulty, and so on in infinitum.

III. As the idea of an empty space and an action at a distance is scarcely possible in the present condition of our knowledge (at least, it does not help to clear a monistic view), I postulate for ether a special structure which is not atomistic, like that of ponderable matter, and which may provisionally be called (without further determination) etheric or dynamic structure.

IV. The consistency of ether is also peculiar, on our hypothesis, and different from that of ponderable matter. It is neither gaseous, as some conceive, nor solid, as others suppose; the best idea of it can be formed by comparison with an extremely attenuated, elastic, and light jelly.

V. Ether may be called imponderable matter in the sense that we have no means of determining its weight experimentally. If it really has weight, as is very probable, it must be so slight as to be far below the capacity of our most delicate balance. Some physicists have attempted to determine its weight by the energy of the light-waves, and have discovered that it is some fifteen trillion times lighter than atmospheric air; on that hypothesis a sphere of ether of the size of our earth would weigh at least two hundred and fifty pounds.

VI. The etheric consistency may probably (in accordance with the pyknotic theory) pass into the gaseous state under certain conditions by progressive condensation, just as a gas may be converted into a fluid, and ultimately into a solid, by lowering its temperature.

VII. Consequently, these three conditions of matter may be arranged (and it is a point of great importance in our monistic cosmogony) in a genetic, continuous order. We may distinguish five stages in it: (1) the etheric, (2) the gaseous, (3) the fluid, (4) the viscous (in the living protoplasm), and (5) the solid state.

VIII. Ether is boundless and immeasurable, like the space it occupies. It is in eternal motion; and this specific movement of ether (it is immaterial whether we conceive it as vibration, strain, condensation, etc.), in reciprocal action with mass-movement (or gravitation), is the ultimate cause of all phenomena. [Ernst Haeckel]

See Also