Edwin Howard Armstrong, a lesser-known genius, changed the face of broadcasting with his invention of FM radio in 1933. This technology reduced static and improved sound quality, providing clearer audio for listeners. Despite his innovative contributions, Armstrong faced fierce legal battles over his patents with major corporations. His perseverance ultimately led to the widespread adoption of FM radio, enriching the listening experience for millions. Armstrong’s legacy endures in every radio broadcast today.

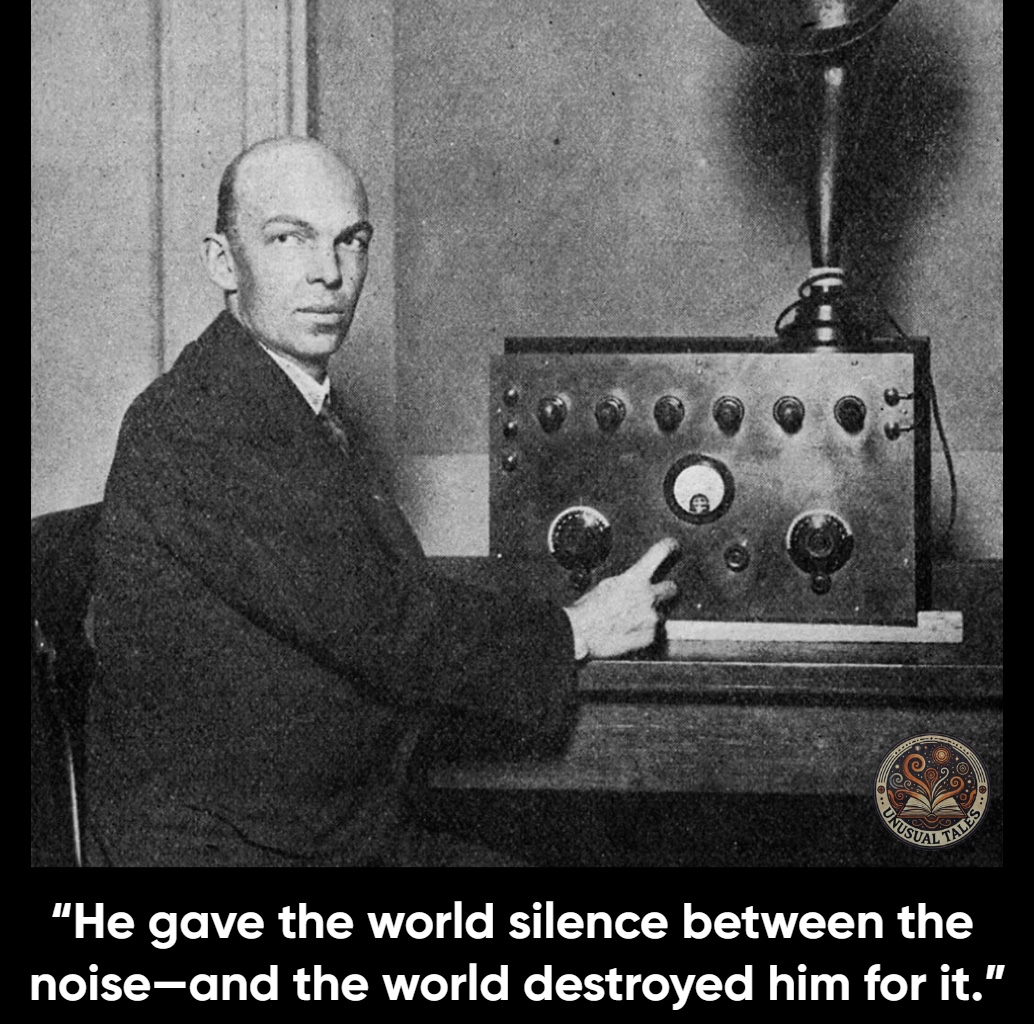

On November 6, 1935, an engineer named Edwin Howard Armstrong stood before the Institute of Radio Engineers in New York. His paper carried a plain title: “A method of reducing radio disturbance through a frequency modulation system.”

What he unveiled was anything but plain. Armstrong had invented FM radio—a way to deliver sound without the crackle and static of AM. For the first time, voices and music could be heard with breathtaking clarity.

It should have been his triumph. Instead, it became his undoing.

Armstrong was no stranger to invention. He had already given the world the regenerative circuit and the superheterodyne receiver, technologies that made radio practical and reliable. But every breakthrough brought him into conflict with powerful corporations—AT&T, Westinghouse, and above all, RCA.

FM threatened RCA’s empire. They had poured fortunes into AM and weren’t about to see it eclipsed. Armstrong built his own FM network on frequencies between 42 and 49 MHz—a revolution in the making. But in 1945, after heavy lobbying, the FCC reassigned the FM band to 88–108 MHz, instantly making Armstrong’s system obsolete. Years of work were erased with the stroke of a pen.

Worse followed. FM stations were restricted to lower power, crippling their reach. RCA pushed television instead, while Armstrong was dragged through endless, ruinous lawsuits. His brilliance was buried under corporate pressure and legal battles.

On January 31, 1954, at 63 years old, Armstrong—exhausted and broken—penned a farewell letter to his wife, Marion. Then he stepped from the 13th floor of his New York apartment.

Yet every time we tune in to FM, we hear his legacy. The clear notes of a song, the clean tone of a human voice without static—that was Armstrong’s gift. He gave us silence between the noise.

History may have tried to silence him, but his invention speaks for him still.

November 5, 1935. New York City.

Edwin Howard Armstrong stood before the Institute of Radio Engineers with a paper titled "A Method of Reducing Disturbances in Radio Signaling by a System of Frequency Modulation."

Then he turned on his invention—and the room fell silent.

Not because nothing was happening. Because for the first time in history, radio was silent. No crackle. No static. No distortion. Just pure, crystalline sound. A voice came through his speakers as clearly as if the person were standing in the room. Music played without the hiss and pop that had plagued every radio since Marconi.

Armstrong had invented FM radio. And he'd just made every AM station in America obsolete.

It should have been his triumph. Instead, it became his death sentence.

Armstrong wasn't some amateur tinkerer. He was already one of the most important inventors in radio history. In 1912, he'd invented the regenerative circuit, which made radio receivers actually practical. In 1918, he created the superheterodyne receiver—still the foundation of nearly every radio and TV today. He'd made radio work when everyone else was still struggling with the basics.

But every invention put him at war with the corporations that controlled American radio: AT&T, Westinghouse, and especially RCA, led by the ruthless David Sarnoff.

When Armstrong demonstrated FM in 1935, RCA had a problem. They'd invested millions in AM radio infrastructure. They owned the patents, the stations, the equipment manufacturers. FM threatened all of it. And unlike Armstrong's earlier inventions—which they could license or steal—this one couldn't be controlled. FM was fundamentally different, fundamentally better, and it made their entire empire vulnerable.

So they destroyed him.

Armstrong built his own FM station network on frequencies between 42 and 50 MHz. It worked beautifully. FM stations began appearing across the country. The future Armstrong had imagined was happening.

Then in 1945, after years of intense corporate lobbying, the FCC made a decision: FM radio would be moved to a new band—88 to 108 MHz.

On paper, it was a technical adjustment. In reality, it was sabotage. Every FM receiver Armstrong and his allies had built became useless overnight. Every station had to rebuild from scratch. Years of investment, thousands of radios, an entire network—erased with the stroke of a regulatory pen.

The FCC also limited FM stations to lower power, crippling their reach compared to AM. RCA pushed television instead, framing FM as obsolete before it even had a chance. And then came the lawsuits—endless, exhausting patent litigation designed not to win but to drain Armstrong's resources, energy, and will.

For years, he fought. He spent his fortune on legal fees. His health deteriorated. His marriage strained under the pressure. The man who had revolutionized radio three times was being systematically destroyed by the industry he'd helped create.

On the morning of January 31, 1954, Edwin Howard Armstrong put on his overcoat, hat, and gloves. He wrote a note to his wife, Marion. Then he opened the window of his 13th-floor Manhattan apartment and stepped out into the winter air.

He was 63 years old.

Marion would later say that RCA didn't just take his inventions—they took his life.

But here's what they couldn't take: the technology itself.

Eventually, FM won. Not because corporations wanted it, but because it was simply better. Today, nearly every radio station broadcasts in FM. Every time you hear music without static, every time a voice comes through clearly, every time you tune to 88.1 or 107.9—that's Armstrong's invention.

He never got to see it triumph. He died believing he'd failed, that the corporations had beaten him, that his life's work had been for nothing.

He was wrong.

Every song you've ever heard on the radio clearly—without crackle, without distortion—exists because a brilliant engineer refused to accept that static was just "the way radio is." He imagined something better. He built it. And when the powerful tried to bury it, his invention survived anyway.

Edwin Howard Armstrong gave us the sound of clarity in a world of noise. And though the corporations silenced his voice, they couldn't silence what he created.

The frequency may have changed. The stations may have been rebuilt. But every time you turn on the radio and hear music the way it was meant to be heard, you're listening to the legacy of a man who deserved so much better than what the world gave him.

See Also