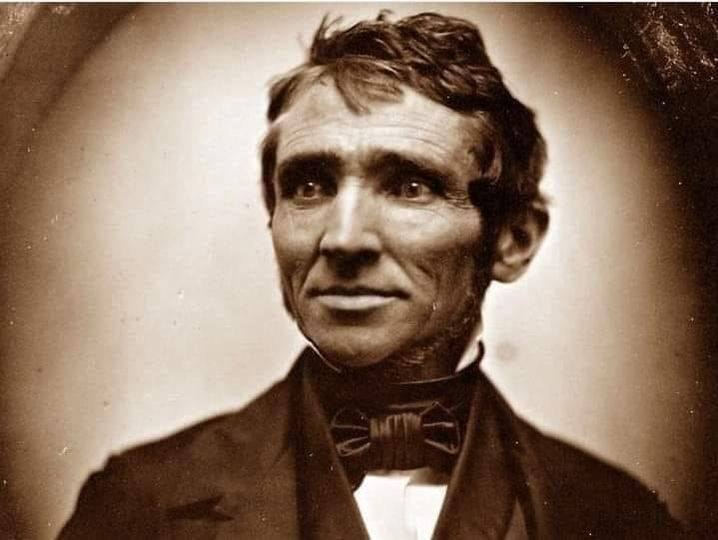

Charles Goodyear left school at age 12 to work in his father’s hardware store in Connecticut. At age 23 he married Clarissa Beecher and soon afterwards the couple moved to Philadelphia, where Goodyear opened a hardware store of his own.

Goodyear was a competent merchant, but his passions were chemistry, materials science, and invention. In the late 1820s he became particularly fascinated with finding and improving practical applications for natural rubber (called India rubber). His experimentation would change the world, but Goodyear’s path to success would be challenging.

In 1830, at age 29, Goodyear was suffering from health issues and his rubber experiments (which he had funded by borrowing) had not been successful. By the end of the year his business was bankrupt and he was thrown into debtor’s prison. It was an inauspicious beginning to his career as a scientist and inventor.

The principal troubles with finding commercial applications for natural rubber was that the material was inelastic and was not durable, decomposing and becoming sticky depending on temperature. Goodyear was determined to find a chemical solution to overcome those issues, beginning his experiments while in jail. After numerous failures, his breakthrough came when he tried heating the rubber together with sulfur and other additives. In 1843 he wrote a friend, “I have invented a new process of hardening India rubber by means of sulphur and it is as much superior to the old method as the malleable iron is superior to cast iron. I have called it Vulcanization.”

Goodyear filed his patent application for vulcanized rubber on February 24, 1844 (one hundred eighty years ago today) and the patent was issued four months later. It is thanks to vulcanization that rubber can be used to make tires, shoe soles, hoses, and countless other items. It was one of the most profoundly important technological achievements of the 19th century.

So, Charles Goodyear became wealthy as a result? Unfortunately, no. He continued to struggle financially for the rest of his life, embroiled in litigation with other inventors over the validity of his patent, preventing him from profiting from it. Meanwhile, his wife Clarissa contracted tuberculosis and much of the family’s income was devoted to her medical expenses and extensive travel in search of a cure. Clarissa died in 1848 at age 39, leaving six children, between the ages of 4 and 17.

At age 54, while still struggling to defend his patents and commercialize his invention, Goodyear married 40-year-old Mary Starr (who had not previously been married) and the couple would go on to have two children together. It too was a happy marriage, but Goodyear was not destined to long enjoy it.

Suffering the adverse effects of years of exposure to dangerous chemicals, Goodyear collapsed at a hotel in New York City on July 1, 1860, dying later that day. At the time of his death, he was 59 years old, penniless, and deeply in debt.

The Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company, founded in Akron, Ohio by Frank Seiberling nearly 40 years later, was named in honor of Charles Goodyear. Neither Charles Goodyear nor anyone in his family was connected with the company.

Reflecting on Goodyear’s achievements, the historian Samuel Eliot Morrison wrote, “The story of Goodyear and his discovery of vulcanization is one of the most interesting and instructive in the history of science and industry.” But, as he added, “It is also an epic of human suffering and triumph, for Goodyear's life was one of almost continuous struggle against poverty and ill health.” Goodyear himself was philosophical about his failure to achieve financial success, writing that he was not disposed to complain that he had planted and others had gathered the fruit. “The advantages of a career in life should not be estimated exclusively by the standard of dollars and cents, as is too often done. Man has just cause for regret when he sows and no one reaps.”

In 1830, a man named Charles Goodyear sat alone in a prison cell—not because he committed a crime, but because he couldn’t pay his debts. The world saw him as a failure. But Charles saw something else: possibility.

He had become obsessed with a strange, messy substance—natural rubber. At the time, it was nearly useless. It melted in summer, cracked in winter, and couldn’t be trusted for anything important. But Charles believed it could be more.

Even behind bars, he kept experimenting. With borrowed tools and scraps, he worked day and night. In 1839, after countless failures, he accidentally spilled a rubber-sulfur mixture near a hot stove. The result? Vulcanized rubber—flexible, durable, and weatherproof. For the first time, rubber could be used in shoes, machines, and eventually… tires.

He patented the process in 1844, but instead of fortune, he faced copycats and courtroom battles. He lost money. His wife Clarissa died. His children lived in hardship. Still, he kept going.

Charles Goodyear died in 1860—sick, broke, and largely forgotten.

But his invention outlived him.

In 1898, a businessman named Frank Seiberling founded a tire company—and named it Goodyear, in honor of the man who made the modern rubber industry possible.

Charles never saw it. He never made a fortune. But every car, every tire, every road that hums beneath our feet owes something to the man who refused to quit.

Sometimes, greatness isn't rewarded in a lifetime.

Sometimes, it’s what we leave behind that changes everything.